Shemlan - A Deadly Tragedy

A couple of years after Shemlan - A Deadly Tragedy was first published, I found a sub-folder in my laptop's big mess of writing folders that contained a tiny snippet of text - an idea I'd jotted down at some stage. It was dated early 2004 and the Word doc in contained no more than:

Today I have been alive a little over an hour. The sea is very blue outside the window of my bedroom, which makes up most of one side of the room. The bed sheets are white and crisp, and they feel good.

It was an odd thing to find - particularly as Shemlan - A Deadly Tragedy, which was originally written in 2011 starts:

Jason Hartmoor has been alive a little over an hour. He has recovered from his recurring nightmare and turned the damp side of his pillow to face the mattress. He lies, luxuriating in the bright light streaming through the window overlooking the sea. It takes up most of the length of the room. The bed sheets are white and crisp. Every opening of the eyes is a bonus, a thrill of pleasure. Sometimes he tries to stave off sleep, lying and fighting exhaustion until the early hours. It is becoming increasingly hard to push back the darkness. These days he’s lucky to hold out beyond midnight.

The idea seems to have stuck around, no?

Shemlan - A Deadly Tragedy is about Jason and his lost love, and how his search for her before he dies of cancer goes terribly wrong, but it’s really about pain and loss, missed opportunities and decisions that shape lives. And it’s also about how state actors shape the lives of the people they use and manipulate to achieve their ends. There’s tremendous sadness in the book, and that sadness is layered as far as Jason is concerned: an unremarkable diplomatic career, a failed marriage, the destruction of his reputation and now cancer - Jason doesn’t really have an easy time of it.

At the core of the book is Jason’s lost life, the brief splash of colour he enjoyed in Lebanon as a young man, before the years turned him to unyielding stone. And that splash of colour was provided by his time studying as a young man at MECAS…

Beirut’s British Spy School

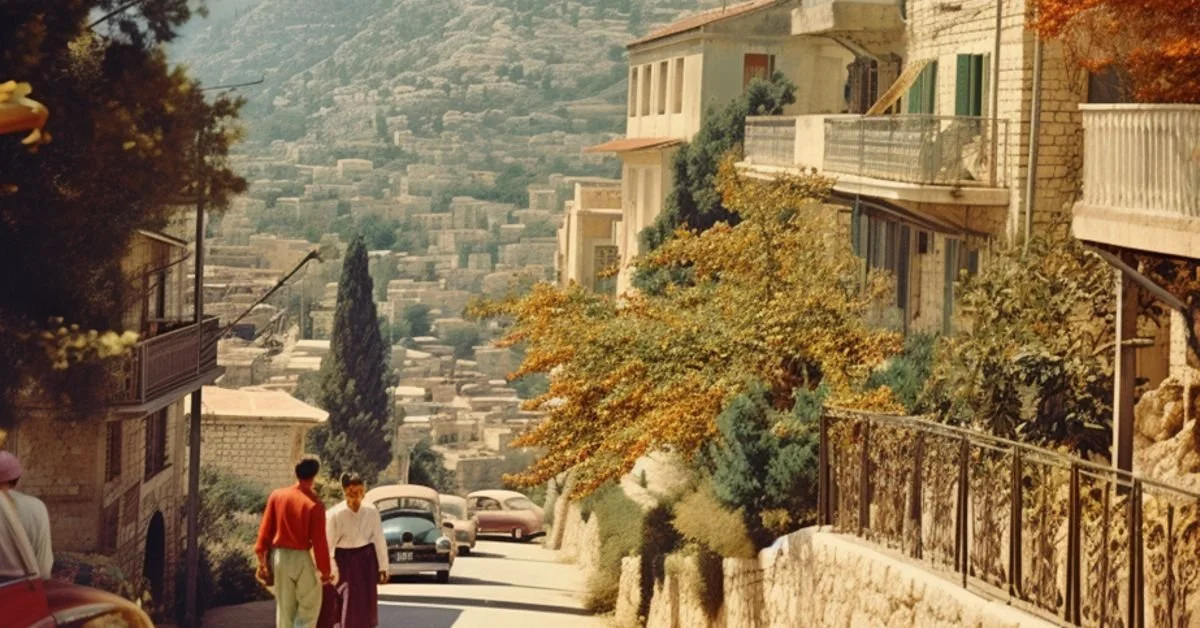

The concept of MECAS - the Middle East Centre for Arab Studies - has long fascinated me. Somewhere up there in the Chouf mountains above Beirut was a building that had for thirty years housed the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Arabic language school - known to the Lebanese as the British Spy School. Founded by Bertram Thomas and closed by the Lebanese Civil War, MECAS is an enigma and a minor marvel to me. It was from here the infamous George Blake was taken to London to be arrested on his arrival, finally unmasked as a Russian double agent, in 1961. The Lebanese, unsurprisingly, refer to it as the British Spy School.

The idea of setting a spy thriller around someone who had studied at the school - around the school itself - had long nagged at me. I bought books about the school and sought out memoirs written by people who had studied there, life-long diplomats like Ivor Lucas, whose self-published memoir of his career was to inform Jason Hartmoor's mostly unremarkable diplomatic existence. Eventually, on a misty, rainy spring morning, I travelled up into the mountains with pal Maha and we tottered around the dripping village of Shemlan looking for the school. Or rather Maha tottered, wearing her usual mad heels and complaining that I was responsible for ruining her McQueens as we squelched around.

She found my comment about how she should have worn trainers unhelpful for some reason.

The locals didn't think much of being asked about the spy school by some Egyptian chick with a camera-toting Brit old enough to be her dad in tow. But we eventually tracked it down. I've been back to Shemlan a few times now - the village is lovely, nestling in the mountains high above Beirut, uphill from Aley and Bchamoun, home to a few shops, the mildly famous Cliffhouse restaurant and an orphanage.

Looking out over Beirut from Shemlan never fails to take my breath away. The city is spread out like a glimmering carpet below, the airport runways sitting by the infinite blue Mediterranean.

It’s a bit of a hike up the mountains past Choueifat - very much the journey Jason took as his battered Mercedes taxi groaned up the hilly road.

Lunch at The Cliffhouse is a fairly traditional Lebanese affair, you can sit by the window popping pistachios and drinking Al Mazas as you look out over Beirut below, dishes appearing from the kitchen with satisfying regularity to populate the table. The restaurant itself is fairly large, a favourite meeting place for couples being 'discreet', but also a popular place at weekends. You’ll often be joined by a noisy party filling one of the long tables set out in the conservatory, celebrating one of life's events with cloudy glasses of arrak.

I had actually started writing Shemlan just before I published Olives - A Violent Romance. The book was shelved, paused about halfway through, while I got publishing Olives and Beirut out of my system. Originally called Hartmoor, the title was quickly changed when I discovered Sarah Ferguson's 'planned' historical novel of the same name was scheduled to publish in 2015. Having sent Beirut bobbing into the wide open sea in 2012, I took up the reins on Shemlan again in 2013 and finished the novel in a mad burst of frenetic activity, pumped on death metal and alternately smacked down by Arvo Pärt like a twisted druggie shredded by a mouthful of French Blues chased down with slugs of chilled vodka and warm dark rum.

And just in case you're interested, yes - I do know precisely what that feels like...

The story of Shemlan was, from an early stage, fated to travel to Estonia. We went to Tallinn for a magical week a few years back and I dragged Sarah across town to the British Embassy so I could photograph it for use in the book later - as it turns out, Lynch never does go to the Embassy to fall out with the ambassador in the final version of the book and so I didn't need the Embassy at all, but you can never be too careful.

Sadly, the other major location for Shemlan was Aleppo and the marvellous C14th Ottoman souk has been destroyed. In the overall devastation the last two years have brought, the loss is a small one, I know.

An odd footnote of interest to absolutely nobody but me is that the Urfalee church of St George's in Aleppo was somewhere you could still hear very early plainchant - the root of all European music lived on in the preserved practice of the Urfalee community. I use the past tense only because I don't know if it - and they - are still there.

The little green orthodox church (Estonia is the most secular country in Europe - you don't get a lot of working churches there!) down by the port in Tallinn is also somewhere you can hear Estonian Orthodox singing, a rare and beautiful sound that is not only similar to the haunting plainchant echoes of Aleppo, but also the inspiration for Pärt's sparse, spine-tingling music. And it was to the aching soundscape of his 'Fur Alina' I finished writing the last few pages of Shemlan - A Deadly Tragedy.

Aleppo’s souk was timeless, ancient and bustling with the manic energy that it sustained over hundreds of years. It was totally destroyed in the Syrian Civil War.